Friend Scope in C#

Introduction

I’m a fan of expressive domain design when I build projects. As such, I believe that classes should be encapsulated such that they convey the intent of their usage.

Some common examples are things like:

- Readonly Properties that are set by a constructor

- Private members and methods

- Private constructors that are called only by factory methods on the class

- Private nested classes that do some kind of special work

- Opaque interfaces (where the implementing classes are actually private)

C# has some useful features for implementing the above including interfaces, nested classes and scopes like private, protected and internal.

But there is something missing from that list: friend.

C++ allowed you to declare a friend class, which was able to access the declaring class’ private members and methods. Although often abused for testing, there are some legitimate cases for doing this, such as moving your factory methods outside of the class.

I also encountered a case of needing a friend when I was building a domain such that one class, FooContainer had an AddFoo(Foo foo) method and it became apparent that I wanted to strictly limit access to AddFoo to a single class - in this case Foo itself. This is because I could ask a Foo to link itself to it’s FooContainer and it would set the bi-directional association. So basically I wanted only one entry point into mutating the Foos contained in my FooContainer and that was via Foo. In C++ this is as simple as adding Foo as a friend of FooContainer - this is not however possible in C#.

The closest built in feature is InternalsVisibleTo which allows another assembly to access this assembly’s internal scoped classes, members and methods - but this is supposed to be a cohesive domain and I don’t want an assembly per class, thanks.

You can of course solve this problem using reflection - but that’s nasty… unless you could somehow provide some kind of runtime verification and of course still provide some form of static type safety. Which is exactly what I did :P

Magic

The principle of friend scope is that the callee controls who can access the resource, guaranteeing that only the intended callers can access it.

The natural way of doing this is C# is of course an attribute.

[AttributeUsage(AttributeTargets.Method)]

public sealed class FriendAttribute : Attribute

{

public FriendAttribute(params Type[] friends)

{

Friends = friends;

}

public Type[] Friends { get; private set; }

}This lets to decorate a method and indicate the types you wish to grant access to it:

public class FooContainer

{

[Friend(typeof(Foo))]

private void AddFoo(Foo foo)

{

//...

}

}You then of course need something to actually invoke this private method reflectively. My chosen route was to define a Friend base class, the reasons for which will be explaned shortly:

public abstract class Friend

{

public object Target { get; private set; }

protected Friend(object target)

{

Target = target;

}

protected void Invoke(params object[] args)

{

// Checks target method for friend attribute against caller

// Does reflective invocation on target

}

}You can checkout github for a full source on how it does the check and invoke.

The last piece of the puzzle is: How can I provide at least some type safety for invoking this method while still keeping the target method truly private?

I solved this problem by defining a private nested proxy 1:

public class Foo

{

private class FooContainerFriend : Friend

{

public FooContainerFriend(FooContainer) : base(FooContainer)

{

}

public void AddFoo(Foo foo)

{

base.Invoke(foo);

}

}

public void Link(FooContainer container)

{

Container = container;

new FooContainerFriend(Container).Add(this);

}

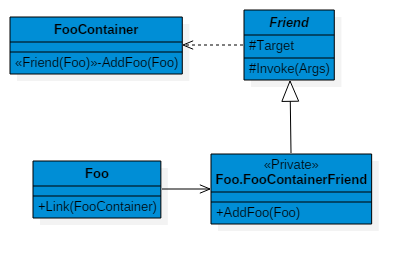

}The above is represented with a UML class Diagram as follows:

Class Diagram: Foo adds itself to FooContainer via the FooContainerFriend

Class Diagram: Foo adds itself to FooContainer via the FooContainerFriend

Analysis

The above scheme exhibits the following properties:

- Only the intended classes can access the

Friendannotated methods (enforced byFriend.Invoke) - The proxy is not visible to classes other than the intended friend

- You get intellisense on the friend call

- The usage of the friend method is still navigable by the IDE (F12 on your target type for the friend attribute)

- Adding new “friends” is trivial: Create a proxy inheriting from friend and copy and paste the desired signature

- The friend client has a type safe interface (this is actually only against the proxy, but it is possible to do a type test at startup with some static test allocation, or write unit test against friendly method invocation)

- Your friends can be polymorphic if you like, allowing you to target entire hierarchies through a base class and interface

Conclusion

I’ve demonstrated the ability to provide friend-like semantics in C# in order to allow for domains which encapsulate rules that restrict access to methods based on specific client types.