Business Process Flow Framework for MVC - Part 2

Abstract: A state machine based process framework for web - Strongly Typed Process Defintions and how they are coded

In my previous post I covered the basic architecture of the process framework I wrote for MVC.

In this post, I’ll cover the details of implementing the processes (or statemachines) and what these look like in code.

Introduction and Recap

On our journey thus far, I’ve motivated my choice for a state-machine based process framework. My approach describes strongly decoupled controllers and processes and a mapping layer which routes controllers actions to processes.

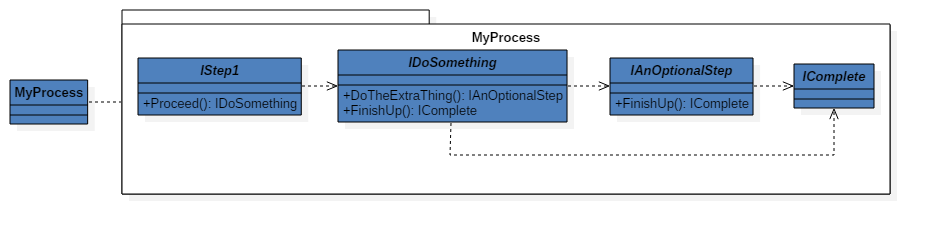

Referring to the two figures below, I’ll be covering the details of how a process is implemented - so specifically the Process, ProcessModel, ProcessStep and ProcessMapping components.

Components: The process manager consumes to mapping in order to correctly route process transitions from the API controllers. The

Components: The process manager consumes to mapping in order to correctly route process transitions from the API controllers. The Process and ProcessStep classes implement any process logic and control process flow.

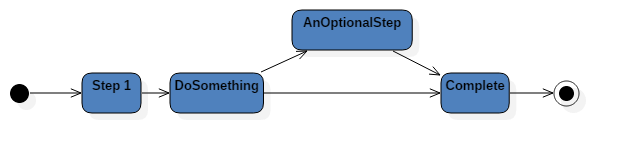

States: A sample process that we’ll implement.

States: A sample process that we’ll implement.

Strongly Typed Processes

Strong typing allows the compiler to spot inconsistencies, and allows the runtime to prevent the program entering an invalid state. These characteristics can be useful when you want to define rigourous processes (or wizards) that the user cannot bypass.

So how does one use strong typing to define a process?

In this case I have exploited the return types of method calls to define the transitions of the statemachine. This means that the method names directly indicate the state transitions and that the method return types indicate the state which the process moves to after transition. This can be illustrated below:

States: Interface types which indicate the implementation of the sample process

States: Interface types which indicate the implementation of the sample process MyProcess. The packaging indicates that the interfaces are nested types of MyProcess

Because the methods are the transitions and the return types are the new states, it is not possible for any state other than those explicitly allowed by the developer to be entered into and that this can be checked for and guaranteed by the compiler.

The nesting of the types also represents a somewhat convenient packaging since the process type itself completely owns the process classes.

So what does it look like in code?

Implementing the previous class diagram will give us something which looks like the below. I have included the framework interfaces which the components must inherit from in order to be consumed as well.

public partial class MyProcess : IProcess

{

public interface IStep1 : IProcessState

{

IDoSomething Proceed(Step1ViewModel model);

}

public interface IDoSomething : IProcessState

{

IAnOptionalStep DoTheExtraThing(DoSomethingViewModel model);

IComplete FinishUp(DoSomethingViewModel model);

}

public interface IAnOptionalStep : IProcessState

{

IComplete FinishUp();

}

public interface IComplete : IProcessState { }

}What I particularly like about this presentation is that this is a living document which describes the process. This semantic document cannot be out of date and can be transformed into a more paletteable form as well - such as a process diagram. It’s also worth pointing out that these are interfaces which represent the contract - allowing me to define them elsewhere in concrete types. Hypothetically, one could use a tool to manage the above code in their code base.

We also see “view models” being introduced, which of course encapsulate the frontend requests that are pushed down into the process layer. These view models are of course part of the contract of the process. They can actually be regarded as Data Transfer Objects.

The Process Meta Data

So now that we have the raw definition of process states and transitions, we still don’t know things like:

- What view do I display for the state?

- Which state is the initial state

- How does this process bind to my API controllers

- How do I provide friendly user information to indicate the process state?

My chosen approach to solving this problem is to supply metadata to the class which can be consumed by the framework.

The Initial State

We annotate the initial state with an [InitialState] annotation. This attribute also requires an argument for an APPI controller type. The framework uses this attribute to know what the entry point into the process is.

So our initial state then looks like:

[InitialState(typeof(MyApiController))]

public interface IStep1 : IProcesState

{

IDoSomething Proceed(Step1ViewModel model);

}View Bindings

Next we need to annotate each state with some kind of view mapping so that the process then knows how to display each state on the frontend. we do this with the [View] attribute, which needs a type for the view controller and an action on said controller. If you’re using T4MVC, you can using the automatically discovered constants to refer to the controller methods.

There is also another view related concern which process steps mus tbe annotated with, which is the meta-data for friendly names on the frontend. We can add this using the [State] attribute in order to indicate the “label” and the “order” of the step.

Our state interfaces now look like:

[View(typeof(MyViewController), MyViewController.ActionNameConstants.Index)]

[State(Label = "Do Something", Order = 0)]

public interface IDoSometing : IProcessState

{

IAnOptionalStep DoTheExtraThing();

IComplete FinishUp();

}Transition Bindings

And of course we need transition bindings - some way for the API controllers to link back to the methods exposed on the step interfaces. These are provided with the [Transition] attribute, which, like the view bindings, needs a controller and a method name. These are then consumed by the the framework to reconcile API method calls into process state machine method calls.

There is also an optional TransitionStereoType argument for the transition attribute. Given that most processes have a next, next, next flow, you can set this transition as the typical next, back or even exit step. This is consumed by the front end when we ask for the “next step” from the framework, instead of having to directly specify it in the frontend.

[View(typeof(MyViewController), MyViewController.ActionNameConstants.Index)]

[State(Label = "Do Something", Order = 0)]

public interface IDoSometing : IProcessState

{

[Transition(typeof(MyApiController),

MyApiController.ActionNameConstants.DoExtra)]

IAnOptionalStep DoTheExtraThing(DoSomethingViewModel model);

[Transition(typeof(MyApiController),

MyApiController.ActionNameConstants.Complete,

TransitionStereoType.Next)]

IComplete FinishUp(DoSomethingViewModel model);

}Consuming the Bindings

To illustrate, your view for this state can now have a button that looks something like this (note the Url.GetNext):

<button onclick="@Url.GetNext(Model, "$ViewContext().viewModel.toPostModel")">Next</button>The razor template doesn’t need to know what the URL to post to is, because it can ask the process manager when rendering the template. If we change the process flow, next is still next - we don’t neccesarily care where exactly it goes. It is worth noting however, that for branching flows you can of course still reference any other API call.

Similarly, your API controller only actually needs one method call:

[HttpPost]

public virtual FinishUpRequest DoSomething(DoSomethingViewModel model)

{

var processModel = ProcessManager.Instance.Transition<MyProcessModel>(model);

return processModel.MapToFinishUpRequest();

}Your APIs need only delegate the call for transition onto the process manager. The type parameter is merely a convience since the Transition method returns the current model state for the process. Any invalid transitions will of course also be be thrown out by the process manager. In this case, the MapToFinishUpRequest would likely be an extension method, although could just as readily be a member method on the model itself. This is not a violation of the decoupling, since the process model and view models are already contracts. Any decoupling and transforms can ery happily be implented in the API layer.

Most importantly, I don’t have duplication of my process flow through my system - I only have a single definition of hwo states move between each other.

Implementing the Concrete States

Finally we need to provide a concrete class that actually implements the process model. This is just about trivial, below is an example:

public partial class MyProcess

{

[Serializable]

public class DoSomething : ProcessStateBase<MyProcessModel>, IDoSometing

{

private void DoTheThing(DoSomethingViewModel model)

{

//Service Calls, transforms, etc...

}

public IAnOptionalStep DoTheExtraThing(DoSomethingViewModel model)

{

DoTheThings(model);

return new AnOptionalStep();

}

public IComplete FinishUp(DoSomethingViewModel model)

{

DoTheThings(model);

return new Complete();

}

}

}Contractually, our steps are required to return implementations of the interfaces specified in the defition, otherwise we get compile time errors. Applications usally also don’t do too much work here, because it usually gets delegated off to some Business Logic Layer Service. The ProcessStateBase simply has some basic plumbing for the process, such as a generically typed member named Model that the process’ internal “transient” state can be stored in.

Conclusion

This post outlines what the code that implements the process framework looks like. It demonstrates the interfaces with annotated meta-data that represents a map of the entire process that allows a Process Manager to bind the underlying business process to application views and API controllers.

Of interest is that we’re able to provide strong typing that allows the compiler to alert us of process violations, and also we need to know very little about the process from the API controllers and the Razor view Templates.